Bruce Bell, History Columnist –

I had an uncle in Sudbury who not only was a Mason, but he was also an Elk, a Toastmaster and a member of the Independent Order of the Foresters (IOF). My mom used to say Uncle Bert belonged to so many men’s groups to have an excuse to get out of the house every night of the week.

These benevolent men’s groups – steeped in ritual, ceremony and fancy regalia – came into their own during the Victorian era. The rise of the Industrial Revolution expanded leisure time, letting the groups flourish within the working and middle classes.

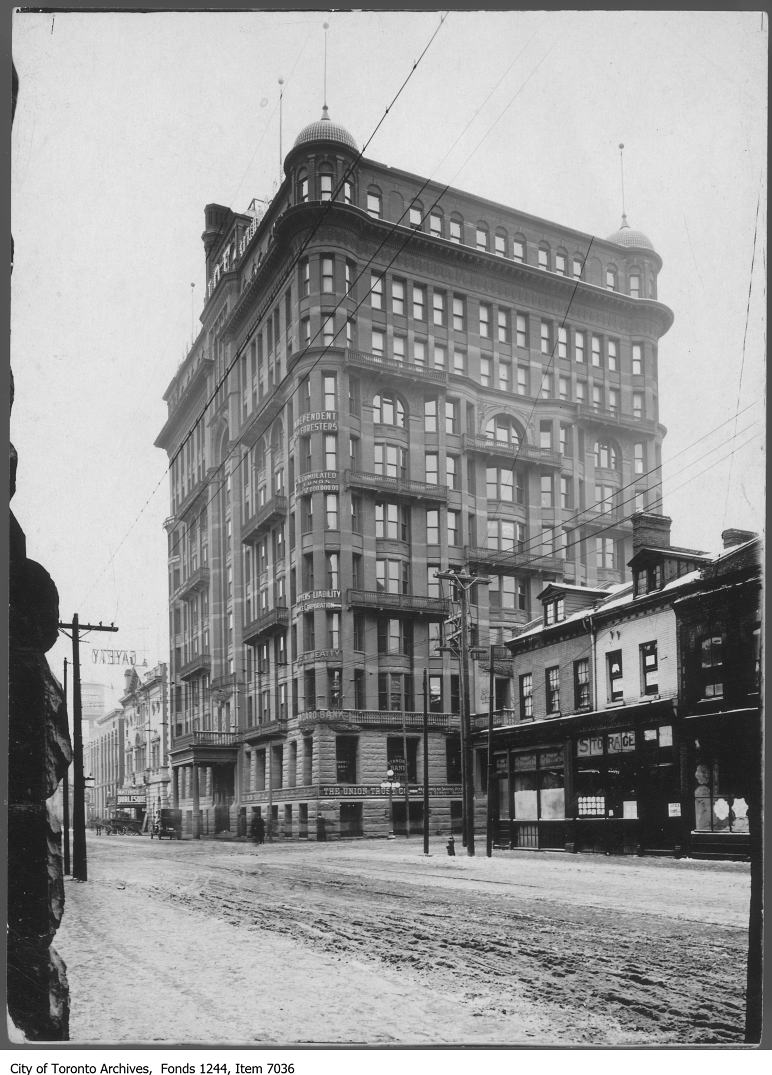

Toronto embraced the concept of men’s societies in a huge way. The city was to have the tallest building in the British Empire as home to Foresters, and Mason chapters aptly meeting in a Temple Building.

The Temple Building on the southwest corner of Bay and Richmond Streets, built by Canadian-born architect George W. Gouinlock, had the fastest elevators in town to entice business. Built in 1895 at a then remarkable height of nine storeys (a tenth was added in 1901) the Temple had richly tiled floors and hand-carved paneling with ornamental doors. The main office eventually had a gilded replica of Edward VII’s coronation chair.

Its brick and stone exterior walls measured four feet thick at the base and an astonishing 18 inches at the ninth floor. This not only made the building’s construction a grueling process but its demolition in 1970 an equally difficult process.

The Globe and Mail wrote about the destruction of this colossal building:

“Want to see a monument destroyed? Go down to the corner of Bay and Richmond streets and watch them make gravel out of the Temple Building. It won’t go easily or prettily because it wasn’t built with destruction in mind.

“It was intended to last like the Pyramids, one of the wonders of a young country, a great stone tribute to an Iroquois who became supreme chief ranger of the Independent Order of Foresters in 1881.”

The Iroquois referred to was Oronhyatekha, born in 1841 in the Six Nations Reserve near Brantford who ultimately became Supreme Chief Ranger of the Foresters Order. Tireless efforts by Oronhyatekha (who always insisted on being called by his Mohawk name rather than the anglicized Peter Martin) made it possible for the Temple Building to be constructed.

At this time private clubs that dotted the landscape of Toronto and Canada were restricted to mostly white men. But through his charm, wit and indomitable spirit, Oronhyatekha rose up the ladder rapidly and became an exception to the rule when he joined the IOF in 1878. So beloved was Oronhyatekha that after his death in 1907 a life-size bronze statue of him stood inside the Temple Building.

Construction of the Temple Building made Bay Street a fashionable address to locate businesses, and with the opening of the New City Hall (now Old City Hall) in 1899 these two great stone monuments complemented each other, cementing Toronto’s reputation as the ‘Queen City of the British Empire.’

But after the Second World War and a trend to modernize office space downtown, the Temple Building was marked for demolition. In 1954 the IOF moved out and in 1970 the building ‘intended to last like the Pyramids’ was torn down.

During its halcyon days, the Temple Building was one of the great social hubs of Toronto. In its ornate Assembly Hall well-heeled members hosted dances, meetings and conventions.

I have a vague memory of the old Temple Building. On our yearly jaunts to Toronto, and because my uncle was a member of the IOF’s Sudbury chapter, we would drive pass the old Temple with its huge IOF sign on top and say, “There’s Uncle Bert’s building!”