By Andre Bermon

The City of Toronto has been ordered to scale back its designs for a Heritage Conservation District (HCD) in the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood.

In a landmark decision issued July 27, the province’s Local Planning Appeal Tribunal concluded that the HCD Plan’s prescriptive nature did not conform to the planning framework governing development in the city. This resulted in amendments by the Tribunal that revised or deleted several of the plan’s preservation guidelines, including sizeably reducing the HCD boundaries.

City solicitors are now considering what action to recommend. Few options are available, but the real question confronting supporters of the HCD is how likely will the city take further legal action.

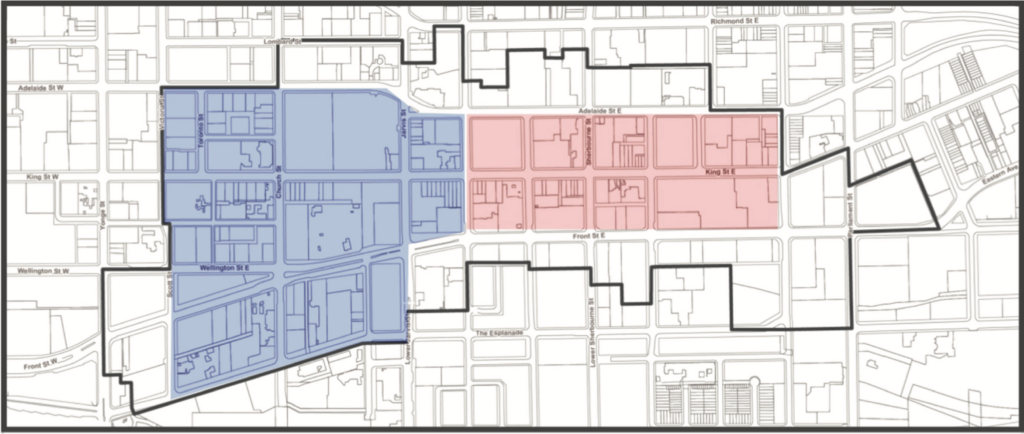

City Council approved the St. Lawrence HCD Plan in November 2015 after years of study and review. Concern over rapid development diminishing the area’s historic character was the impetus to propose a 25-block heritage district under the Ontario Heritage Act, from Yonge and Wellington at the west, south to Front and Jarvis, and east to King and Parliament. This area includes valuable real estate and some of Toronto’s most cherished monuments.

A consortium of developers led by Allied Properties REIT immediately appealed the plan to the Ontario Municipal Board, which in 2017 became the LPAT. Four years of procedural maneuvering culminated in a 14-day hearing in November 2019 that saw nine appellants and city solicitors debate the plan’s binding guidelines.

According to the LPAT decision, the goals of the HCD Plan’s three main standards for new “built form” – specifying step-backs for buildings, street wall heights and angular planes – would be better realized without its mandatory policies.

The appellants claimed the rules’ rigidity would prevent City Council from considering development proposals that met the HCD objectives in an alternative form. The LPAT agreed, ordering the step-back, street wall height and angular plane prescriptions deleted from the HCD Plan.

Suzanne Kavanagh, chair of the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Association’s planning and heritage committee, told the bridge that heritage policies cannot be realized “through the lens of planning” alone. In other words, certain aesthetic nuances vital to the appearance of old neighbourhoods are hard to defend in a pedantic court-like setting.

“That’s why we are still pushing for the 45-degree angular plane,” said Kavanagh. “It’s not that we are anti-development, it’s that, particularly on King Street East, [we want] to have some sky view … to see what’s left of the heritage buildings and/or facades.”

An assertion supported by the city that the Tribunal was not persuaded by.

The other major point of contention was the proposed HCD boundary, which developers argued was not rationally defined to reflect cultural heritage values.

Michael McClelland of ERA Architects Inc., who provided witness statements on behalf of Allied Properties, called for the heritage district to be reduced to the 10 original blocks of the pre-1837 Town of York, centred on King Street, and the old “civic reserve lands” that contain landmark buildings such as St. Lawrence Market and St. James Cathedral.

St. Lawrence Market.

Photos: Tania Correa

St. James Cathredral.

St. Lawrence Hall.

This boundary revision would exclude structures such as the Consumer Gas building, now 51 Division, and 33 Yonge Street, a 13-storey glass office tower. The two buildings were added to the HCD to anchor its most easterly and westerly portions with key intersections and to envelop adjacent territory such as the site of Upper Canada’s first parliament and Berzcy Park.

Appellants argued that the HCD should evoke a sense of place, “based on the underlying historic organization of the cultural heritage values of the area.” They cited a directive of the City’s policy manual for heritage conservation districts that “It is not appropriate to include unrelated areas solely for the purpose of making the district larger or to extend control.”

The Tribunal found that the City’s proposed boundary lacked historic motive and ordered the revision based on Allied’s recommendation.

In response, Kavanagh stated, “They are trying to make it as small as possible. They knew if they gave us nothing, we would go wild. So, they gave us the bone.”

“[When] we started off with a study area, we chose the boundaries of the SLNA [as a starting point]. It’s just geography, it has nothing to do with the association…This is the third chop [the boundary] has gone through. And now it’s basically King Street … that’s just not acceptable.”

City Council can take further legal action to defend the HCD Plan. One option is to ask the LPAT board to have another member revisit the case, as was done in a development involving the Berkeley Church.

In an email to the bridge, Tamara Anson-Cartwright of city planning stated, “City Planning is moving ahead with the necessary revisions of the HCD Plan …,” suggesting that additional legal action may not be on the table.

So far, the City has spent $250,000 on the HCD study, while preparing for the hearing over four years and arguing the case likely cost millions of dollars.

Until it is publicly known what action the City is willing take, revisions to the HCD will be on hold until further notice.

“Is it worth it for [the City] to slow down or work faster on this?” pondered Kavanagh. “Are they going to [prioritize] this while working on other HCDs going to the LPAT? Who knows?”