Bruce Bell, History Columnist –

By 1880 Toronto, once a lonely colonial outpost, was poised to be the most brilliant new city in the British Empire, thanks in part to the railroad and an influx of immigrants. Boosting this claim, Toronto embarked on a 20-year building boom that saw some of its most stunning construction projects.

Much of what led Toronto into its golden age of architecture was the spectacular rise of powerful banks. Banking in the mid 19th century was not for personal savings, but almost completely commercial and governmental. Profits were generated by loans to government projects and venture capital for manufacturers and importers.

No bank was then more influential than the Bank of Montreal, founded in 1818 but not allowed in Toronto until 1841, when the Act of Union united Upper and Lower Canada. The first Bank of Montreal branch office here was in a converted townhouse that at time stood on the northwest corner of Bay and King Streets.

In 1845 the bank moved into new headquarters on one of the most sought-after sites in Toronto, the northwest corner of Yonge and Front Streets, the entryway to this grand new city.

Where Meridian Hall (né O’Keefe Centre) now stands was once the site of the Great Western Train Station (1869–1952). Across from that once stood the American Hotel (c.1844–1889) and on the southwest corner came the elaborately detailed Customs House (1873–1920), a masterpiece of white marble.

All this centred on the Yonge Street Wharf (c.1840–1926), the main terminus for people traveling by steamship to Toronto. It jutted out onto Lake Ontario just below Front Street before vast landfill operations filled in the old harbour.

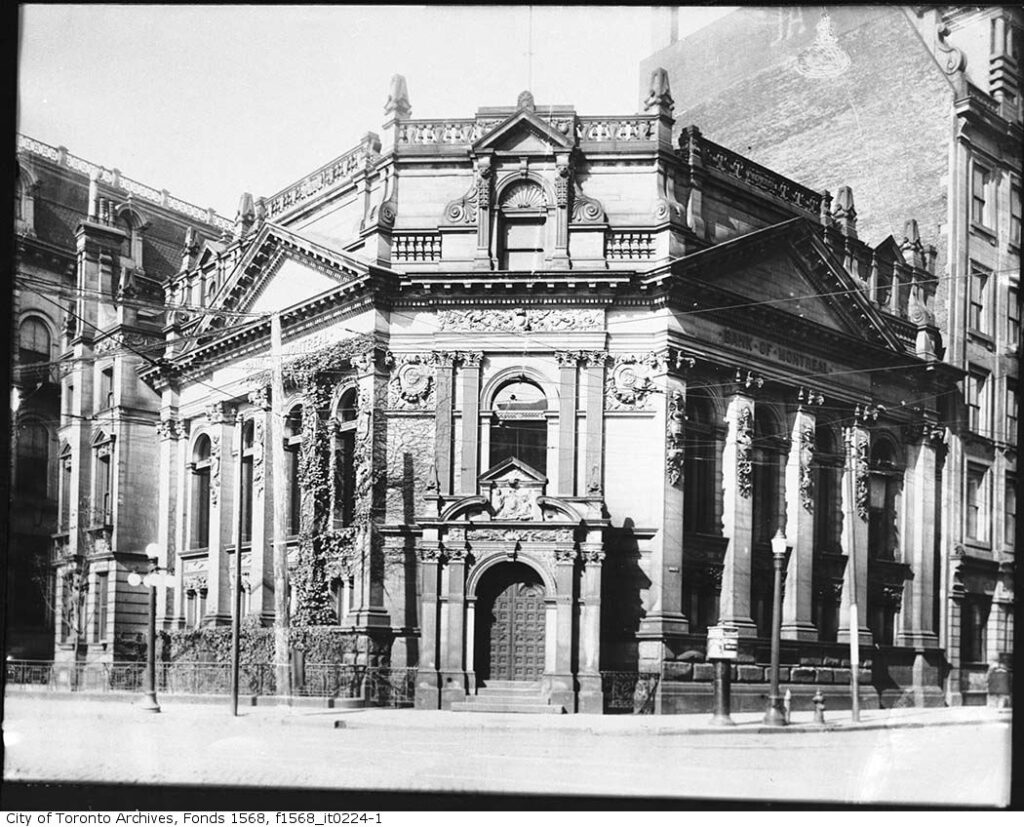

The first Bank of Montreal building on the northwest corner of Yonge and Front, built in 1845, was discrete and formal, fashioned after elegant gentlemen’s clubs in London, England. In 1886 that first branch was torn down to construct what would be the most luxurious and stunning building in the city. The new Bank of Montreal, built by the firm Darling and Curry and completed in 1888, had an interior considered the finest banking hall on the continent.

Bank of Montreal c1890. Image courtesy of Toronto Archives.

When I arrived in Toronto from the wilds of Sudbury in 1972, I wandered into that bank and gasped, as I had never seen anything like it. In the mid 1970s every inch of the original interior woodwork was completely painted white, but it was still a sight to behold.

Miraculously, this building survived the chaos of Toronto’s great postwar urban renewal, when more than 25,000 buildings were bulldozed. However, its days were numbered too unless a new use could be found.

The Hockey Hall of Fame was housed on the grounds of the Canadian National Exhibition in a building opened in 1961 that was starting to show its age. Choosing the former BMO building as its new home preserved the city’s banking and hockey past in a magnificent setting.

The former bank, like a temple, has its own trophies announcing civic virtues carved in stone on its exterior.

On the south side exterior are carved emblems to commerce, music and architecture; on the east are crests to industry, science and literature. To top it off, a statue of Atlas representing strength and sport is poised outside as if holding the building up.

But the stained-glass dome is probably the most magnificent architectural treasure of the former bank. Designed and set in position in 1885 by the Toronto firm of Robert McCausland Ltd., the dome is adorned with finely detailed mythological figures and provincial emblems.

In 1991 Robert McCausland’s great-grandson Andrew was given the task of restoring the dome – just in time. Andrew said, “Some of the glass panels were badly slumped and the glass was beginning to fall out of the lead.”

On June 18, 1993, after a renovation costing $35 million, the rich wood paneling, the detailed murals and exquisite gold leafing of the former bank once again shone as the new Hockey Hall of Fame opened its doors.

Today, this stunning building is undergoing yet another restoration of its exterior. I wish more of such architectural refurbishment had been done in the 1960s and ’70s, for some equally dazzling gems are now gone forever.