By Daryl Gonsalves –

Love it or hate it, every Torontonian has an opinion of the Gardiner Expressway. Ever since the highway’s eastern extension (the Gardiner East) was approved, the project has faced criticism particularly from urban planning circles. Given its significant capital costs and the burden it puts on the City of Toronto capital budget, the return on investment for the Gardiner is not clear.

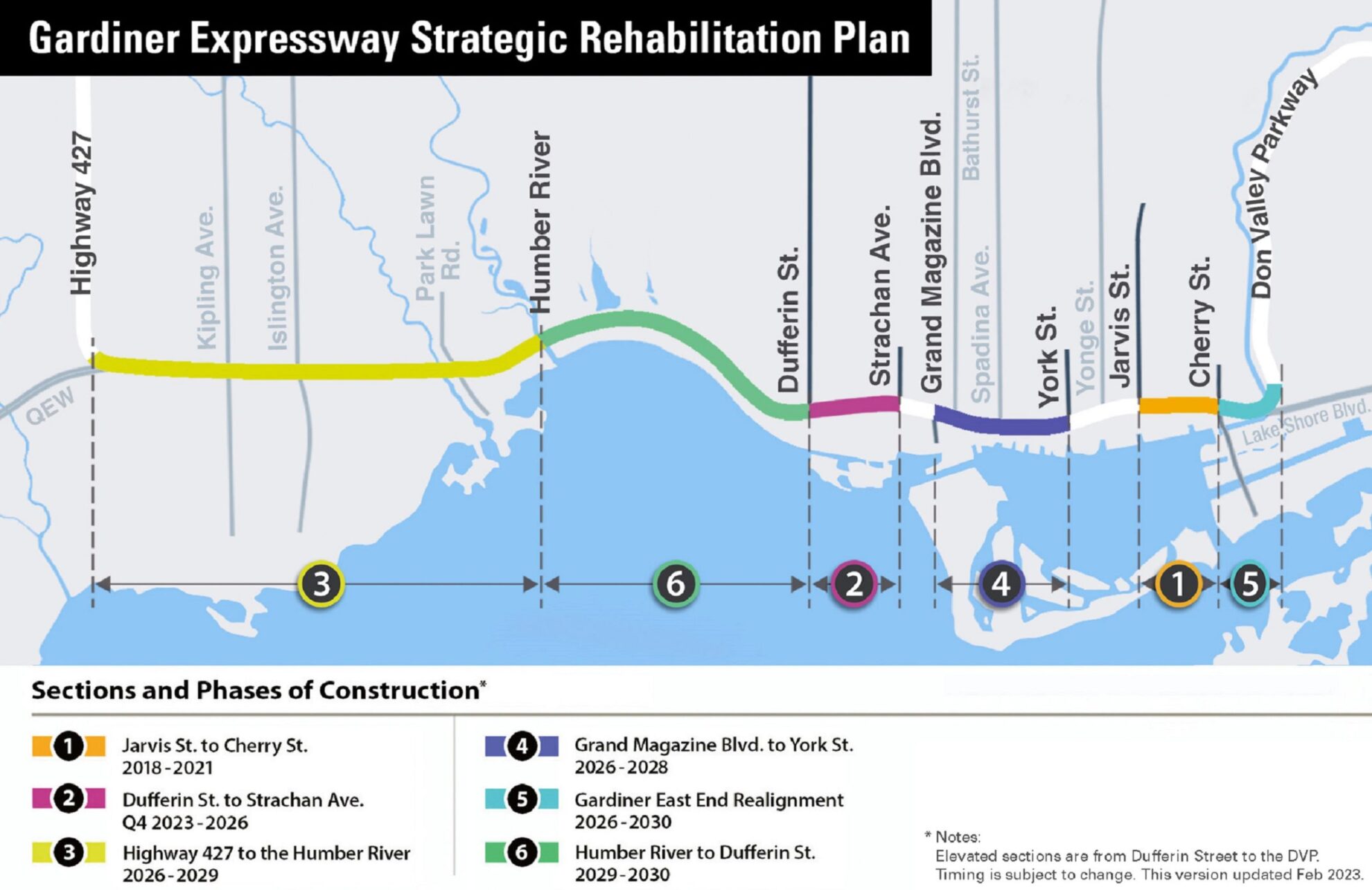

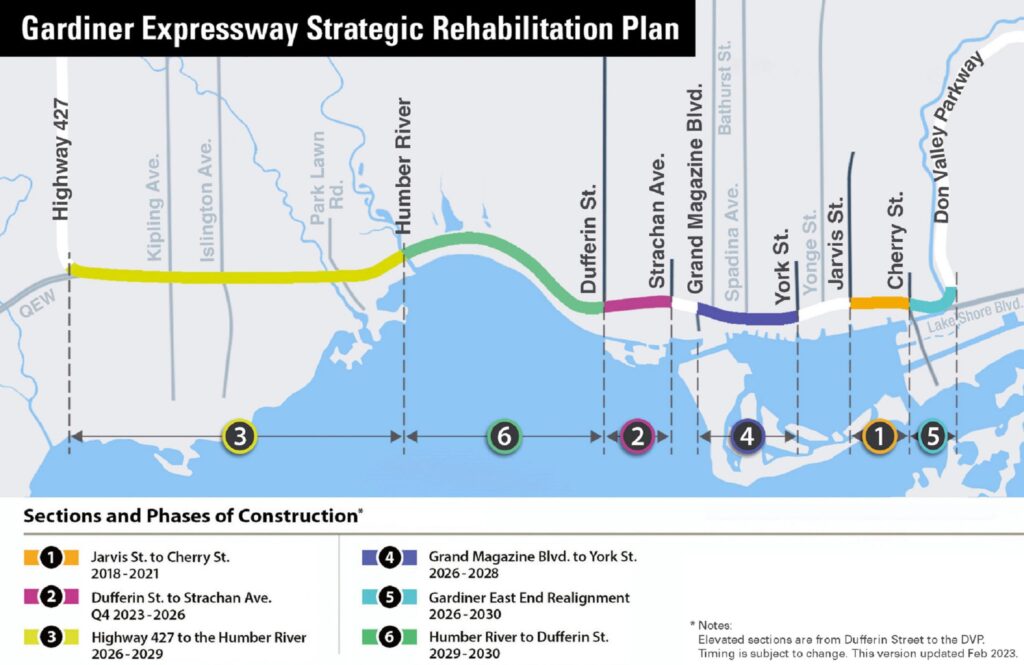

The Gardiner East project, approved by City Council in 2015, proposes to extend the elevated highway eastward by approximately 1.7 kilometres from its current terminus near Leslie Street. Built during the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Gardiner Expressway was meant to accommodate 60,000 vehicles daily. Today, it’s 140,000 vehicles on an average weekday which contributes to significant wear and tear of the aging infrastructure.

During rush hour it’s clear that the Gardiner’s original design has been overcome by user demand. But building more highways won’t solve congestion, as studies have shown that induced demand quickly fills up new road capacity with new drivers, resulting in the same levels of congestion.

In addition, there are many opportunity costs as the drivers who use the Gardiner could take other means of transportation, and the space that the expressway occupies could be devoted to housing or other uses.

On an annual basis, maintenance on the highway costs the City of Toronto $16 million. Despite the City of Toronto’s budget crunch, $2.2 billion in capital spending has been budgeted over the next 10 years to rehabilitate the Gardiner highway as a whole.

Within this budgeted amount, the cost of the Gardiner East is estimated to eat up $1.2 billion.

That said, this project estimate is expected to increase because of the current inflation being experienced in the construction sector. To date, the City of Toronto has already spent $500 million through committed contracts and detailed design work on the Gardiner East.

In the original City of Toronto and Waterfront Toronto report which evaluated options for the future of the Gardiner in 2014, public servants stopped short of providing a formal recommendation which allowed City Councillors to have additional political room to make a decision despite the facts on the ground. Since the 2014 report was published, the Province has made significant investments in transit which may have impacted the findings of the options analysis that was completed. The Gardiner East project should be a cautionary tale on the need to depoliticize infrastructure decision-making processes. A transparent and accountable decision-making process should prioritize evidence-based business cases that thoroughly evaluates the return on investment and the effect of future climate change pressures.

After many failed attempts to ship the Gardiner to the provincial government, which pays nothing to maintain this highway to 905, the City of Toronto must recognize it is a municipal problem. Acknowledging a reality that we are progressing forward with the Gardiner East project, here are some ideas to move forward in a productive manner:

● Convert one Gardiner lane to dedicated bus rapid transit (BRT): This could provide reliable and efficient public transit, reducing congestion with an affordable alternative to driving cars. BRT systems have been successful in cities like Bogota and Istanbul. Given the constant news reports of GO Transit buses stuck in congestion, this is an easy win.

● Encourage carpooling and ride-sharing with reduced tolls or preferential parking for multiple-passenger vehicles. In cities such as San Francisco and Washington, D.C., this change has led to fewer single-occupancy vehicles and decreased congestion. However, it would require Toronto to publicly raise the prospect of vehicle tolling, previously rejected by the province in 2016.

● Develop affordable housing units: Land value around the highway could be used to finance new developments, helping meet the growing demand for affordable housing.

● Promote active transportation: Investing in cycling and walking infrastructure to create safe and accessible commuter routes would help diminish congestion, promote healthy living, and reduce the City’s carbon footprint.