By Ben Bull

As the coronavirus wave reaches its peak and we take our first tentative steps outside, many Ontarians may wonder what life will be like after the lockdown.

Watching the daily briefings of the Premier of Ontario, it’s clear that our journey will be complicated. Testing is not where it needs to be. Protective equipment issues persist, and contact tracing measures are largely ineffective.

On May 19 only 5,813 tests were conducted – way below the province’s target of 16,000 a day. And a recent Toronto Star article noted that up to two-thirds of Ontario’s new COVID cases cannot be traced back to their source.

Traditional contact tracing methods take resources. They rely on call centre staff contacting anyone who has been in close proximity to a newly infected person. However, these methods have sometimes proven problematic. Britain recently hired 21,000 contact tracers, but, as the Guardian newspaper notes, “People hired to contact those exposed … and advise them to self-isolate have reported spending days just trying to log into the online system, and virtual training sessions (have) left participants unclear about their roles.”

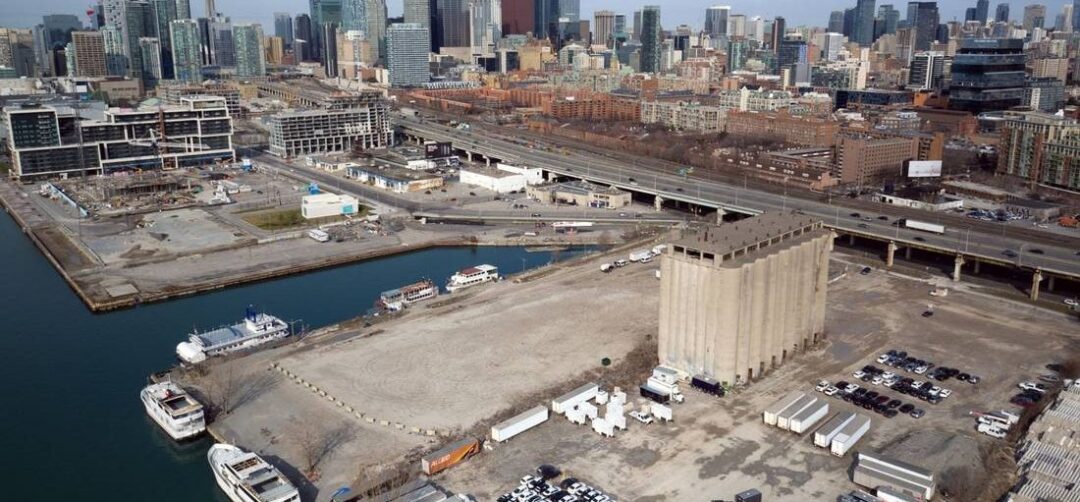

Photo: EPA

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University estimate that the United States would need to recruit and train 100,000 contact tracers to manage their anticipated workload, the Washington Post recently reported.

Five days after Premier Doug Ford announced the first phase of Ontario’s re-opening on May 14, new case numbers surged past 500. Given that it takes five to seven days for symptoms to appear and a few days to process tests, medical officials have suggested that Mother’s Day gatherings (May 10) might have been a source for many new infections.

So how can we effectively track the source of each outbreak, alert those affected and hold back the next wave of infections?

Many cities are supplementing traditional contact tracing with automated tracking. Mobile apps, which use cellphones’ Bluetooth and GPS to identify where you’ve been and who you’ve been with, are being rolled out across the globe. When a positive test is reported, the app alerts the infected person’s contacts. But some apps centralize the collection of healthcare data, leading to questions about how this information will be used, who can access it, how secure it is, and when the data will be purged.

Alberta’s Privacy Commissioner is reviewing the province’s ABTraceTogether app after concerns were voiced. The University of Calgary also recently looked into a number of contact tracing apps.

“None of the apps have convinced us that they were actually privacy conserving,” stated the director of the university’s National Cybersecurity Consortium, Ken Barker, the Calgary Herald reported. “In fact many of them have purposes that went beyond contact tracing. None of them had any real plans about how they would go about managing and looking after the data that they had been collecting.”

Some apps go beyond simple notification. In India, the state of Maharshta’s mobile app, MavaKavach, creates a virtual perimeter around an affected user’s home and alerts authorities if the perimeter is breached.

Adoption rates for mobile contact tracing apps have been low. Singapore’s TraceTogether tool is one of the more widely adopted apps, but just 27% of the population use it. An Oxford University study found that a rollout rate of 60% is required to be successful. And with different apps proliferating, people not using the same tool as those they came into contact with will not be alerted.

So what will happen once we are all outdoors and the rollercoaster curve starts heading upwards again? Will we be sent back indoors? Or will a more robust contact tracing method roll out? Given our current contact tracing and testing challenges, the post lockdown world is likely to be fraught with confusion.