By Coralina Lemos

Corktown historian and author

In a decision dated July 27, 2020, the Ontario Local Planning Appeal Tribunal (LPAT) denied the City of Toronto its proposed boundaries for the St. Lawrence Heritage Conservation District (HCD). Part of the executive summary submitted by preservation staff read, “The St. Lawrence Neighbourhood is one of Toronto’s oldest neighbourhoods, and contains within its boundaries built, landscape and potential archeological resources that reflect the evolution of Toronto from the founding of the Town of York to the contemporary city of today.” Yet in point of fact, the neighbourhood was born 41 years ago and integrated into the Town of York historical boundaries.

Nearly five decades ago, Toronto was suffering from a housing deficit that made it difficult for people with low or moderate incomes to find affordable housing. Thus in 1973, and following revisions to the federal government’s National Housing Act, Toronto City Council adopted the Living Room report as its housing policy, with one key condition: that a site needing revitalization be found in order to qualify for the federal government’s Land Banking Program.

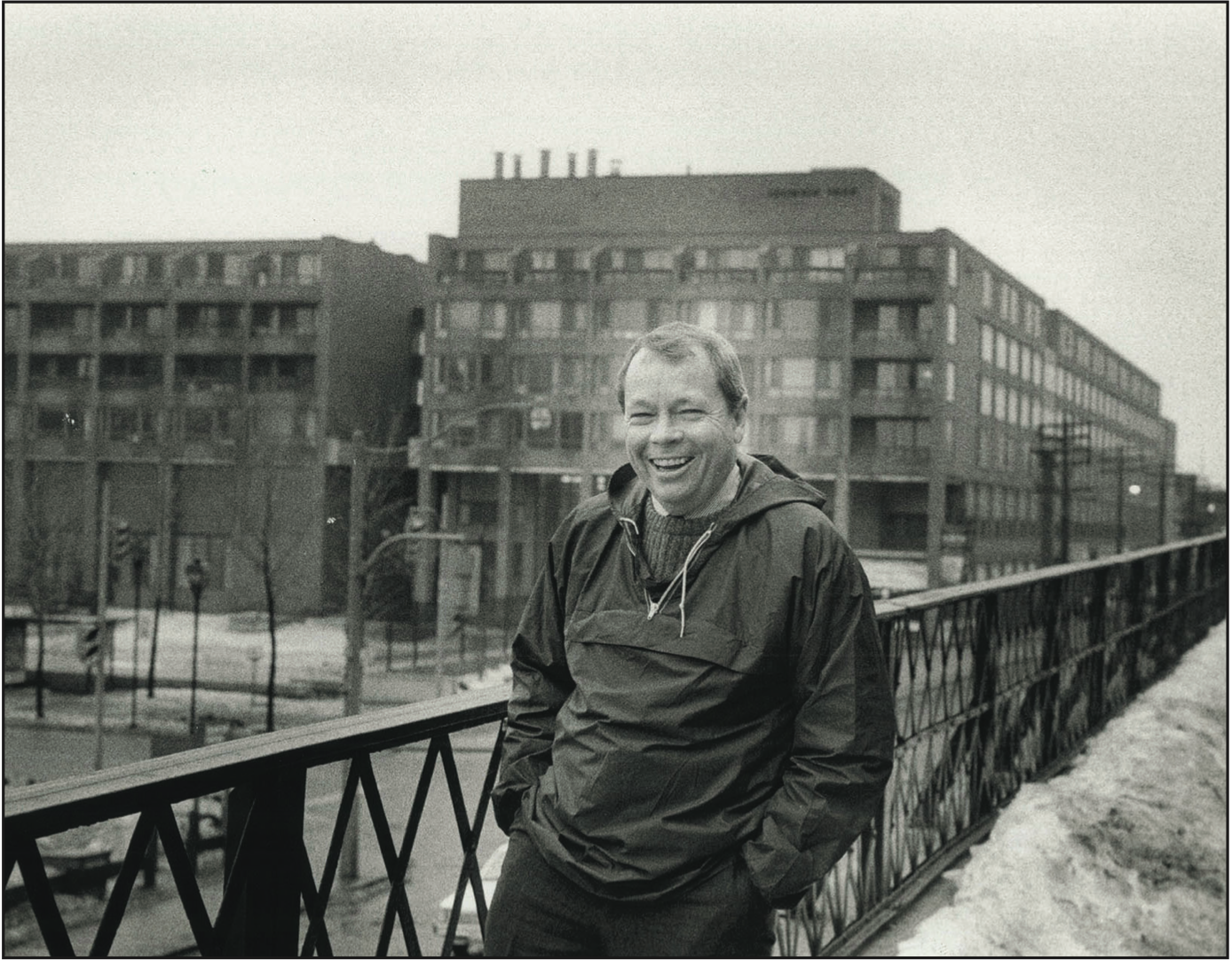

Photo: Courtesy of the TPL

Months later, in 1974, the “Land Banking Proposal: St. Lawrence” confirmed that a land option had been secured and negotiations initiated. Totalling 44 acres of underdeveloped land, the impending district would stretch from the Esplanade (behind today’s Meridian Hall) east to Parliament Street, and from Front Street south to the railway embankment. Destined to be a new integrated neighbourhood within downtown Toronto, the redevelopment was named and designed around the St. Lawrence Market, a destination considered vital to maintaining streetscape character so as to “create a neighbourhood that benefited from nearby historic buildings.”

By the start of 1979, ads began to run in the Toronto Star inviting people to “Come to a Christening!” of the “new St. Lawrence Neighbourhood,” along with a contest to name seven new streets. On Sunday June 3, highlights of the celebratory day included a tour of the Old Town, access to model suites and free TTC service from Union Station. Former Mayor John Sewell welcomed the crowd and announced the winners of the street-naming contest. The completed project was to cost $145 million and projected to house 10,000 people by 1981. As it’s evident, today the St. Lawrence neighbourhood has expanded its moniker far beyond from where it first began.

But as the heritage conservation district proposal started to come to fruition, its outlined boundaries showed conflicts with nearby property owners and neighbourhoods. This became evident in By-law 1328-2015, which illustrates the annexation of 51 Police Division (former Consumers Gas Station A) from neighbouring Corktown, an area identified in the study as being of “special identity”. The overlap did not make sense as following human settlement by First Nations, the area east of Berkeley has a distinct hereditary footprint based upon the establishment of the Government Park Reserve. To make matters worse, the Corktown street sign at the northeast corner of Parliament and Front Streets was replaced with that of the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood.

Following months of anticipation and 14 days of hearings, the tribunals’ written decision agreed with expert witnesses for the appellants stating that six character sub-areas, each with common building typologies, and four periods of significance did not align or support the objectives of the HCD. Consequently, the tribunal ordered the City to revise the boundaries and gave a detailed listing of streets in the redrafted St. Lawrence Heritage Conservation District. And as the tribunal saw no benefit to the inclusion of 51 Division, it was excluded from the HCD plan.

As this narrative continues to unfold, Toronto’s second oldest and often overlooked historic neighborhood of Corktown continues to wait for the replacement of the street sign and its own Heritage Conservation District.