Bruce Bell, History Columnist –

The recent Ward’s Island fire that saw the sad end of its historic clubhouse brought to mind other massive fires in our city. To date, Toronto has witnessed two massive infernos – almost 50 years apart, but both in April – that have been declared Great Fires.

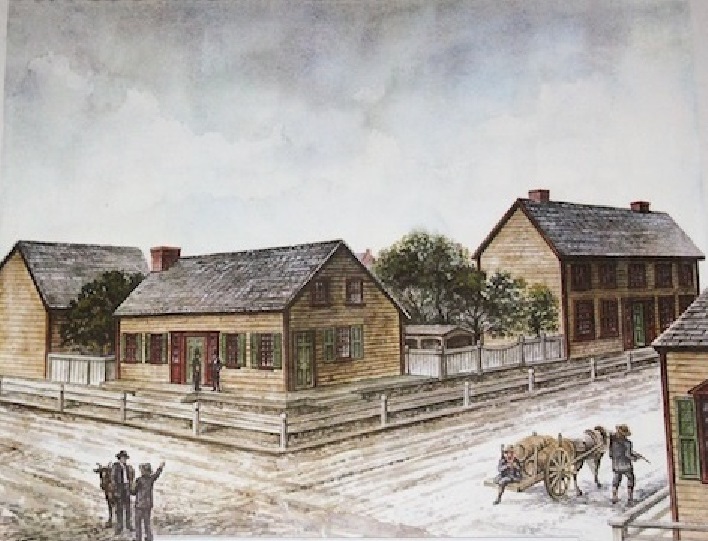

The first was on the morning of April 7, 1849, when the area bounded by Front, Adelaide, George and Church Streets burnt to the ground. This Great Fire started about 1 a.m. in a stable behind a then-popular drinking establishment, Covey’s Inn, on the north side of King Street just east of Jarvis.

It may have started with a cow knocking over a lantern onto a pile of straw, as in the Chicago fire legend, or it could have been deliberate – as half the fires in the 1800s were set on purpose. No one knows for sure, but it grew to become one hell of a firestorm.

The flames leapt from floorboards to tin roofs to wooden sidewalks. As luck would have it, not until it reached St. James Cathedral at King and Church Streets did the city’s fire alarm awaken neighbours to the full impact of the fire.

The heat was so intense by the time it got to St. James that the church’s giant bell swaying high in the belfry rang out only a few times before crashing through the roof and smashing on the sidewalk.

Residents formed a line with buckets stretching down to the lake in a desperate attempt to save what was fast becoming a lost cause. The fire brigade did what they could, hand-pumping water from barrels atop their rudimentary horse-drawn wagons; the few fire hydrants Toronto had were in the other part of town. To make matters worse the water company building burnt to the ground, alongside everything else in the fire’s path.

Amazingly, only one victim died: Richard Watson, trying to salvage what he could from the smoke-filled office of his newspaper, The Patriot.

Toronto changed forever that night, as the present-day St. James Cathedral was built atop the ruins of its predecessor and the old Market was razed to make way for the opulent St. Lawrence Hall. New bylaws were passed prohibiting new wooden structures in the downtown core and requiring brick firewalls between buildings. Some historic firewalls can still be seen jutting up beyond the rooflines in many older buildings still standing in Old Town.

At the turn of the new century Toronto suffered another devastating blaze when the Great Fire of 1904 leveled the area bounded by Melinda Street just south of King, down to the Esplanade, east to Yonge and west to York Street. A total of 122 buildings went up in flames, putting 230 businesses out of commission and 6,000 people out of work.

Archive photo of the aftermath of the great fire of 1904. Looking north on Bay Street. Photo courtesy of Toronto Archives

How that great fire started has never been solved, through some reports at the time thought a stove was left burning at the end of the workday. A night watchman first sounded the alarm at 8:04 pm on a freezing cold night of April 19, 1904, when he saw flames shooting out of the E. & S. Currie Building on Wellington Street just east of Bay Street.

When the alarm came to a firehall, its doors would quickly be flung wide open and reins for the horses would drop into place without delay. Then a steam-powered pumper engine would be attached with its coal-burning kettle blazing as firemen geared up and slid down the hall’s pole. Whipped into a frenzy, the horses would make a mad dash out onto the street, bells a ringing and dogs a chasing all the way to the blaze.

The fire quickly spread. By 9 p.m., with every firefighter in the city on site, the mayor realized this was no ordinary fire and sent telegrams to other cities asking for speedy assistance.

The fire spread up Bay Street destroying everything in its path, but thankfully the newly opened City Hall on Queen Street was saved.

By 11 p.m., the fire had moved south on Bay and reached Front Street, where it swept down to the Esplanade and east towards Yonge Street. By 4:30 a.m., it was declared under control, through the ruins would continue to smoulder for two weeks.

The fire destroyed 122 buildings, and later claimed one victim: John Croft, hired to demolish the ruins after the fire, died when a dynamite charge went off unexpectedly. A laneway in the Annex, between Bordon and Lippincott Streets south of Harbord Street, is named in his honour.

The Great Fire of 1904 was one of the first local news events caught on film, when George Scott grabbed his then state-of-the-art motion picture camera and filmed horse-drawn steam-powered pumper trucks hurtling down Bay Street, followed by children on bicycles waving at the camera.

The city was rebuilt after both of these fires, and in many ways a better metropolis was created. This gives me hope that a new Ward’s Island clubhouse will rise from the ashes.