By Andre Bermon –

Life in the Church-Wellesley community is about to get a lot more crowded.

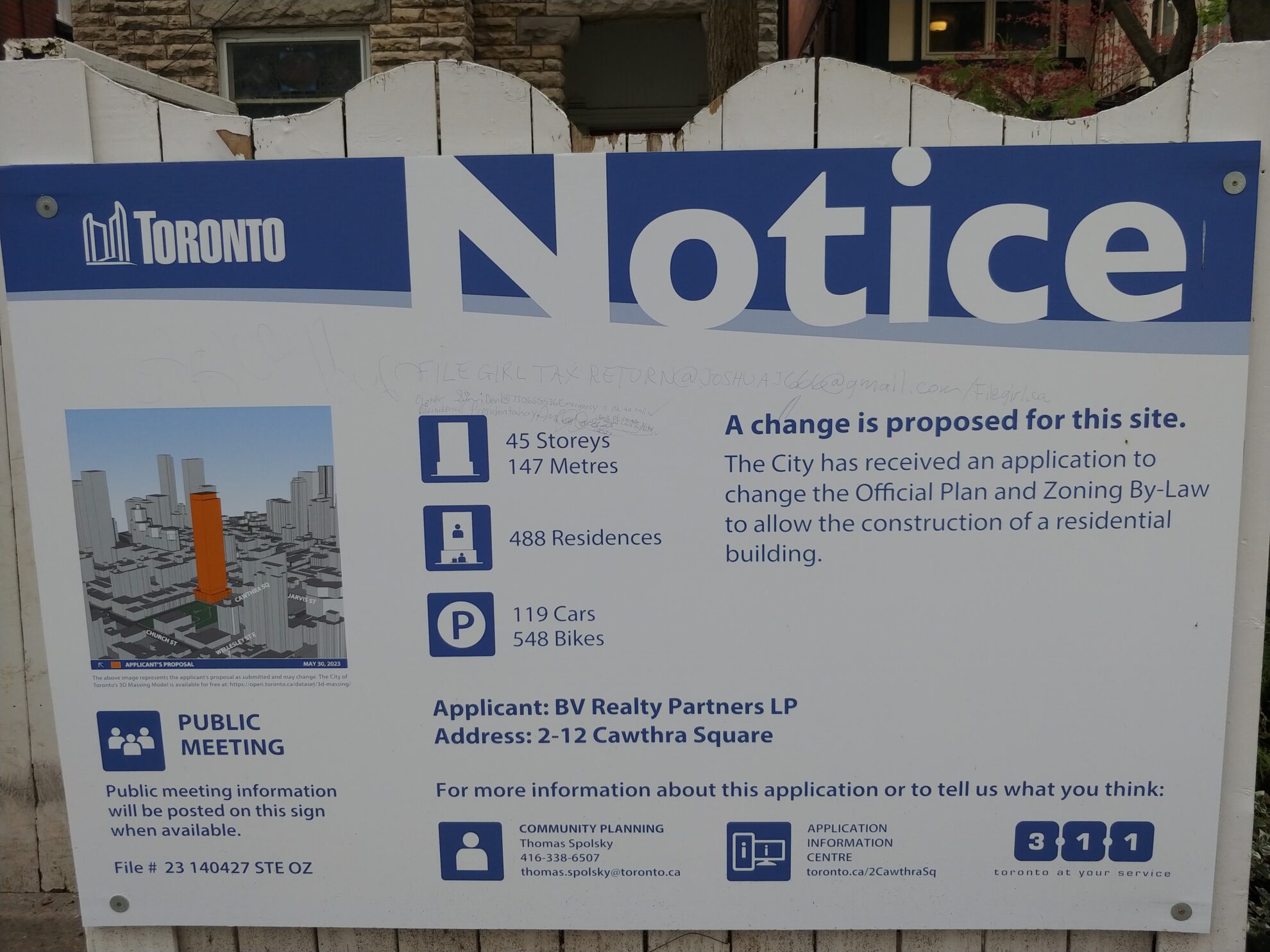

According to the city’s Application Information Centre, within 100 metres of the Church-Wellesley intersection, six residential condominium developments are active. Three of these planned projects are more than 40 storeys high, one of them calling for 56-storeys.

They’re expected to house thousands more people, in a combined 2,246 units.

More homes coming to market may be a welcome response to the city’s growing housing crisis, but current residents worry about such rapid development.

Connie Langille, a member of the Church Wellesley Neighbourhood Association and a Gloucester Street resident since 1985, says the community has already been “coping” with nearly 20 years of condo development.

“It began on Charles Street, and it’s moving its way south. So eventually, it was bound to hit Church and Wellesley,” Langille told the bridge.

New provincial rules have increased pressure on municipalities to respond faster to development proposals, which Langille says undermines community input.

“It does not leave much time for community consultation, if at all. Public consultation is time-consuming and labour intensive. Therefore, [city planning] uses Zoom a lot of times,” Langille said. “Some people think not everybody is heard.” Toronto’s planning process requires a developer to meet with local stakeholders only once, at an hour-long meeting hosted by City Planning and often involving the local councillor and staff. The public is invited to join and give feedback.

Ward 13 Councillor Chris Moise acknowledges the challenges facing the Church-Wellesley neighbourhood. “From day one I have been trying to get more resources in the community,” he told the bridge.

Moise’s office is trying to designate Toronto’s Gay Village as a cultural district, which the city says would result in a program to enhance and coordinate services, resources, technical expertise, and for funding tools to protect, retain and celebrate local culture. Little Jamaica on Eglinton Street West is to become the city’s first designated cultural district, after concerns rose from Metrolinx’s long-delayed Crosstown LRT project, which locals said caused many Black-owned businesses to close. Staff are still reviewing the final consultation on Little Jamaica that was released last September.

Moise says he is also exploring a land trust to protect community assets like small businesses and housing stock. In the Parkdale neighbourhood, the city partnered with local service providers and grassroots organizations to retain 81 single-family homes as affordable housing. Tenants of these buildings form co-operatives to participate in governance and maintenance decisions.

In 2013 City Council adopted new urban design guidelines for several “special character areas” in the downtown core. The Church Street Village Character Area is described as a generally low-rise community with retail at grade and residential and office units above. Some heritage assets have also been identified.

Despite years of intense development, Church Street from Charles to Wood, remains surprisingly untouched. However, proposals on both the northeast and northwest corners of Church and Wellesley, by KingSett Capital and One Properties respectively, would change that.

One Properties cut its 2017 plan to build a 43-storey tower down to 28 storeys, a move lauded by the community for integrating stakeholder wants. But the same can’t be said for KingSett.

KingSett Capital, a private equity real estate firm, is looking to rezone the northeast corner of Church and Wellesley to accommodate a 28 -storey tower. Despite the developer’s efforts, City Council refused the application.

“KingSett sometimes feel like they’re entitled not to follow the rules set out in the in all the guidelines and bylaws… They are very vocal about not intending to comply,” said Langille.

The proposal is likely to end up at the Ontario Land Tribunal for mediation. If the province approves it with little modification, the project could threaten Church Street’s character.

A business owner who leases space on the KingSett property told the bridge anonymously that the project has made him uncertain about his long-term prospects. While happy that the city refused the original proposal, he says it will only delay the inevitable. He and fellow business owners worry about being kicked out when the lease ends, leaving vacant storefronts until construction starts – which can take years.

And what will happen to the residents in the 17 existing rental units? KingSett has stated it will work with the city on “acceptable” tenant relocation and assistance, but the phenomenon known as demoviction can be drawn out and stressful.

According to the CBC, demovictions have been increasing in Toronto. Church Street, with its many row houses and low-rise walk-ups, is particularly vulnerable.

Rama Fayaz, a member of ACORN, an organization helping low- and moderately-income renters, says the city’s rental replacement bylaw needs strengthening. “Tenants have to find temporary housing on their own … and with the private rental market, it’s very difficult.” Some people move as far as Hamilton to find similar rental prices, he added.

When a tenant moves to a new apartment, developers pay ‘rent gap’ assistance (paid in a lump sum covering the entire displacement period) based on a survey of the primary rental market (purpose-built rentals) published annually by Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. Fayaz says the survey does not accurately reflect Toronto’s dynamic rental prices because it doesn’t capture data from the secondary market, i.e., condominium rents.

On April 17 Council agreed to increase the rent gap assistance by considering rental data from buildings built after 2015. For someone demovicted downtown, the new rent gap assistance would be calculated using local rental data, giving a wider range of housing options (with more money) and a better chance to stay in their community. The city says this will make it easier for tenants to secure interim housing, and for owners to get vacant possession and speed construction of replacement housing.

However, the city’s solicitor noted that the province recently gave itself the power to impose limits and conditions on owner compensation to displaced tenants.

Nicki Ward, former provincial Green Party candidate for Toronto Centre and current president of City Park Co-op in the Village, told the bridge that’s it up to the city and local politicians to lobby the province to protect and advance the community. “We need better policing, better clean-ups, better load safety, better mental health support. We have new folks coming in, but we have the same or less community support than before.”