By Bruce Bell –

One of the most celebrated buildings in New York City is the Public Library on Fifth Avenue, a landmark structure as famous as the Empire State Building or the Statue of Liberty. Built in 1897 by the renowned architectural firm Carrère and Hastings, the library is breathtaking, from the iconic stone lions standing guard to the painted ceiling of the famous Rose Reading Room.

At the end of the 19th century, Toronto had structures that equaled, and in some cases, surpassed this library’s stunning radiance.

Toronto had grown from a desolate British colonial outpost of 500 people in 1800 to an imposing city of almost a quarter million by 1900. With that escalation came men of industry and commerce loaded down with new money.

These barons of trade, wanting to leave their mark, hired the leading architects of their day to build spectacular commercial palaces. As Toronto grew, its architecture went from the elegant Georgian as seen today in the Grange of the Art Gallery of Ontario (1816), to the classical St. Lawrence Hall (1850) and the second empire style (Bank of British North America at the northeast corner of Wellington and Yonge Streets, 1872). At the turn of the 20th century came the grandest style of all, the Beaux-Arts.

The New York firm of Carrère and Hastings, came to define the architectural era they lived in, as Beaux-Arts or Beautiful Art, a neoclassical architectural style taught at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. John Merven Carrère and Thomas Hastings, became the preeminent Beaux-Arts architectural firm in North America.

The pair’s first major work was the Ponce de León Hotel in St. Augustine, Florida, built in 1887. A decade later they rose to national prominence by winning the competition for the New York Public Library.

Toronto was to have five Carrère and Hastings buildings, alone or with local partners. Three remain, including Spadina House’s glass and wrought-iron porte-cochère added in 1905.

The most famous Carrère and Hastings building in our city was the Bank of Toronto headquarters, built in 1912 on the southwest corner of King and Bay Streets. Its interior was dominated by a stained-glass ceiling dome, and the exterior by 21 marble Corinthian columns each three storeys tall.

Sadly, the building was demolished in 1964 to make way for the Toronto Dominion Centre. However, bits and pieces of this tour de force, including its main entrance, can be seen at Guildwood Park in Scarborough. A scale model is on display in the present TD Centre banking hall.

The Beaux-Arts movement arrived at the same time as skyscrapers, making some of North America’s early tall buildings even more imposing.

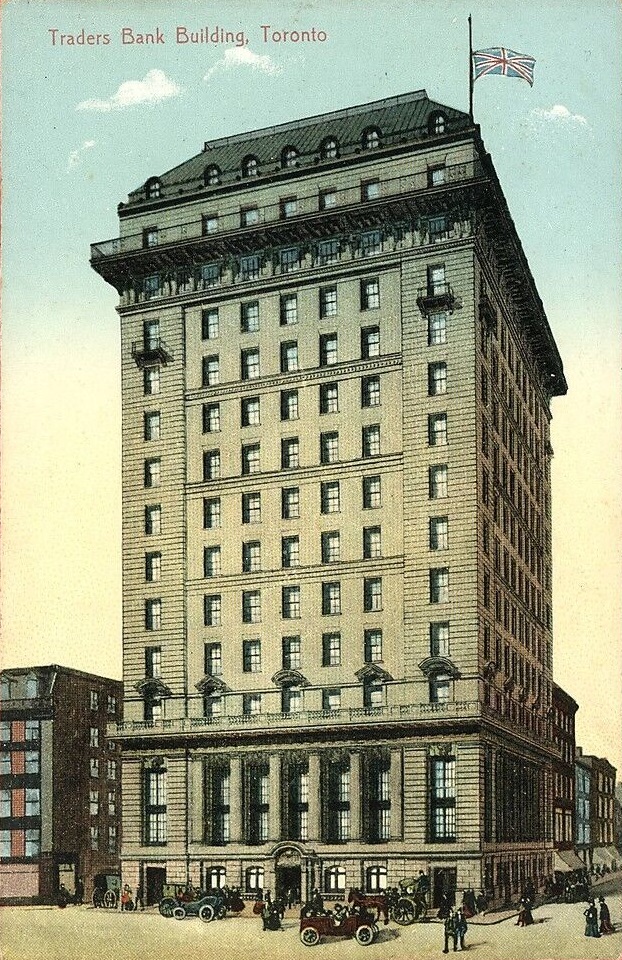

A superb example of a Beaux-Arts Carrère and Hastings skyscraper still standing in Toronto is the Trader’s Bank built in 1905 at 67 Yonge Street. At 15 storeys, it was once the tallest building in the British Empire.

The building’s exterior, with its brilliant terra-cotta frieze of cattle skulls, has recently been cleaned and repaired. But nothing remains of its once stately two-storey banking floor, destroyed during one of many renovations.

However, an Art Nouveau spiral staircase at the rear of the lobby, a masterpiece in wrought iron, managed to survive.

On the northeast corner of Yonge and King is another Carrère and Hastings structure: the Royal Bank Building, built in 1914 by the architectural firm of Ross and Macdonald. After a recent exterior cleaning revealed its original white limestone block façade, it looks like it did a century ago.

With its massive exterior Corinthian columns still standing guard along King and Yonge, it too once had a glorious banking hall of black marble columns and sweeping staircases. Alas, all was gutted in 1959 for a more modern interior look.

While Toronto lost many Beaux-Arts buildings during the 1960s and ’70s, we still have some excellent examples, including the Royal Alexandra Theatre (1907), the 1903 wing of the King Edward Hotel, and the Bank of Montreal (1886) – now the Hockey Hall of Fame.

Arguably the largest Beaux-Arts building still standing in Toronto is Union Station (1927), built by local architect John Lyle. As an associate of Carrère and Hastings, Lyle was involved in designing the New York Public Library, and Carrère and Hastings were partners in Lyle’s Royal Alex.

Carrère and Hastings’ lustrous affiliation lasted from 1885 until 1911, when Carrère was killed in an automobile accident. Thomas Hastings continued on his own, using the firm name, until his death in 1929.

Shifting attitudes in design, including the more streamlined Art Deco in the 1930s and International Modernism in the 1950s and ’60s, led business leaders to disregard the work of Carrère and Hastings as fussy.

Despite its rush to modernize, Toronto has managed to hang on to some Carrère and Hastings masterpieces, almost as a digitus medius or a middle finger to the present.