By Andre Bermon, Publisher –

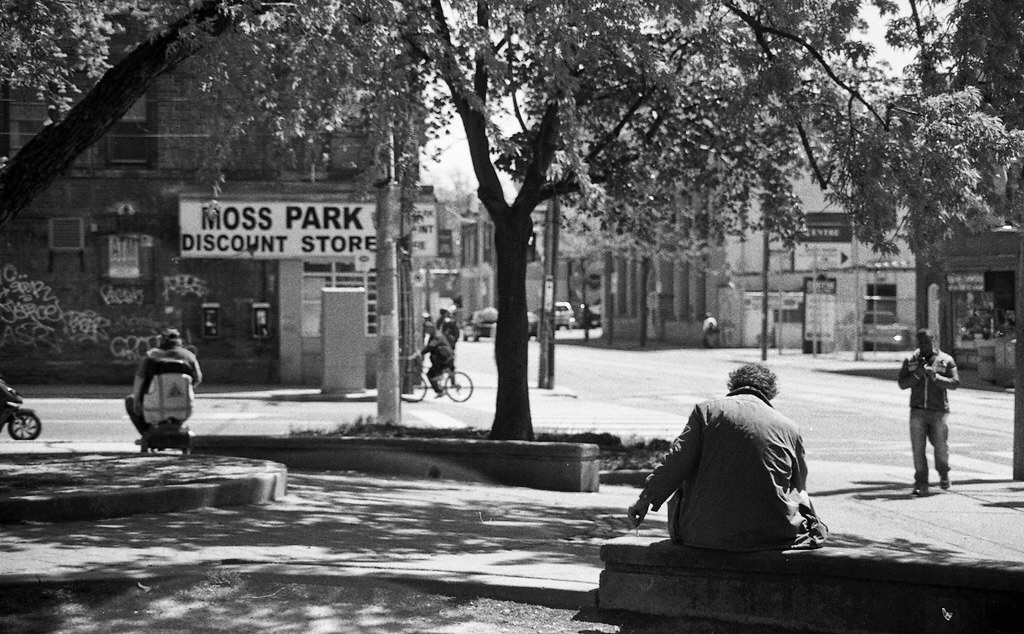

Social challenges in the Downtown East are complex. Homelessness, drug abuse and violence are outcomes of inner-city poverty that Moss Park and the Dundas/Sherbourne community is no stranger to.

For decades the change required to fulfill the basic needs of area residents has passed by this working-class community, in stark contrast to the attention given to other parts of the city, including neighbouring Regent Park.

The political and economic factors that have stilted this neighbourhood’s progress are by no means coincidental. History shows a pattern of policy failure, disinvestment and subsequent Band-Aid solutions from governments designed to maintain the status quo.

The Moss Park and Sherbourne corridor have been ghettoized. This term describes a systematic concentration of homelessness, low-income housing and social services that many have come to depend on.

As David Roberts, an associate professor at the University of Toronto’s Urban Studies program, explained to the bridge, “To use the term ‘ghetto’ without thinking about the processes is problematic. But ‘ghettoize’ indicates there is a decision to invest in certain parts of the city and under-invest in others.”

Conversations with different stakeholder groups in the area reveal similar perspectives.

Residents in Cabbagetown South, which borders Dundas and Sherbourne, experience quality of life problems due to the proximity of significant homelessness and drug use. Their complaints include vandalism, trespassing, theft, and verbal and physical assault.

In one instance, a Seaton Street homeowner woke up to find a naked man injecting himself on the steps of his house. In another incident, an individual masturbated on someone’s front lawn.

These are extreme examples, but nonetheless illustrate anti-social behaviour concurrent with unresolved mental health and drug-related illnesses.

Many of the Cabbagetown South residents who spoke with the bridge have lived in the neighbourhood for two decades or more. All agreed that social challenges in the community have gotten worse.

This perception is partly driven by the large encampment in Allan Gardens. Ward 13 Councillor Chris Moise’s “encampment dashboard,” which tracks the number of tents and people living in the park, as of June 19 counted almost 90 tents – a 200 per cent increase since early April.

The Allan Gardens encampment is a symptom of larger societal problems – in this case, lack of affordable housing and safe and accessible shelter space. It is also congruent with the ghettoized state of the Downtown East. The encampment exists because it is allowed to.

“We have become the dumping ground for all the problems of the city, [because the city] finds that we can put up with it,” said Ontario Street resident John Rider.

Rider thinks the area along Sherbourne has been written off by politicians, and fears things will get worse with the continued proliferation of condo towers. More market-based apartments for people with money could exacerbate the economic divide in places like Moss Park and lead to further conflict between social strata.

Protecting space for those living on the fringes is a goal widely shared by social outreach and mental health care workers. Many support the continued expropriation efforts of 230 Sherbourne, an empty lot and century home near Dundas and Sherbourne, for social housing despite the property being purchased by developer KingSett Capital. There is currently a proposal to build a 47-storey condominium on the property.

Angie Hocking, a community pastor with the United Church who supports poor people, said there has been a concerted effort to push lower-class people into areas “where they can exist.”

She attributes the prevalence of poverty in the Downtown East to other neighbourhoods not supporting people less well off. “It’s not like people [living in the Downtown East] have options. The system creates that reality for them,” said Hocking.

She blames the municipal government and developers for not prioritizing housing for the many who can’t afford Toronto rents.

Outreach worker Lorraine Lam says the city has been “siloing the poor” in smaller neighbourhoods to keep them invisible. Challenges of ghettoization have led to “incredible resilience and survival” of those living in the Dundas/Sherbourne corridor, with impressive support for one another.

“When I look at this neighbourhood, I see a lot of strength and fight with people. They’re fighting to stay alive, and people are fighting to continue to press on,” said Lam.

3 Comments

We live opposite Allan Gardens and have started a committee to come up with innovative solutions to what now call The Garden of Shame. The city doesn’t have any innovative ideas. We’re started an Appeal Letter to present to City Council, once Olivia Chow officially assumes the Mayor’s role. We already have almost 500 Ward 13 signatures on it. We are striving to help move the Allan Garden people into a better situation. No one really wants to live in a tent through the rain, snow, sleet, etc. Hopefully we’ll get the City to help us to help these folks.

This is not an on-line petition. The city doesn’t recognize on-line petitions because anyone, anywhere in the world can sign it and they have no way of validating that it represents the needs of a specific group. Our petition has real signatures, names and addresses. It is time consuming but we want the city to notice and hear the concerns of its citizens.

I hope Mayor Chow takes this petition seriously. Tired townhalls with councillors and police which lead to small, temporary changes and then back to business as usual.