Andre Bermon, Publisher –

Ward 13 Councillor Chris Moise wants to bring back the Queen East Business Improvement Area (BIA) – known officially as the Historic Queen East BIA. Anyone willing to wade into these deep and troubled waters had better come prepared.

The Queen East BIA was established in 2006 by a group of business and commercial property owners with support from the city. The founders had a clear vision: use money from a commercial tax levy to revitalize a depressed and abandoned strip of Queen East, from Victoria to River Streets.

Right from the get-go, the BIA encountered spotty support. Apart from accusations of bad faith (some claimed businesses were purposely sidelined), opponents believed there were too few commercial properties along the linear boundary to sustain a viable budget. The notion of being ‘taxed to death’ to attract shoppers to the mean streets of Queen and Sherbourne was a legitimate concern.

Those against the BIA were ultimately vindicated when a failed budget vote in 2008 brought down the whole experiment barely two years after its creation.

Fast forward to 2024 and Queen East still has an established, but inactive, BIA. To revive it would require buy-in from commercial property and business owners: a majority membership vote to pass a budget.

If you first don’t succeed, try, try again?

The main reason the BIA flopped was that the organization failed to communicate a simple answer to members – why the BIA would be beneficial.

The Toronto Association of Business Improvement Areas describes a BIA as an organization of commercial property owners and business tenants within a defined area who “work in partnership with the City to create thriving, competitive, and safe business areas that attract shoppers, diners, tourists, and new businesses.”

BIAs are financed through levies on all commercial and industrial properties within the BIA’s boundary, based on their assessments. Members elect a Board of Management, which approves a budget that City Council ratifies.

On paper, proposals for improved streetscapes, festivals, capital improvements and fancy marketing campaigns sound enticing. But to the lowly commercial property owner near the corner of Queen and Parliament, who has seen businesses turn over more often than rotisserie chicken, might question the benefits from these pie-in-the-sky ideas. Especially since members would be paying into a scheme they can’t opt out of. (If you own commercial property within the BIA boundary you cannot avoid paying the levy.)

BIAs work in many parts of the city with an established cultural identity (Greek and China town), a robust commercial strip (Yonge Street) or animated streets (Kensington Market). Queen East, sadly, doesn’t have any of that, for obvious reasons.

Take a walk from Victoria to River Street. The biggest plots of land are not commercially owned but are institutional or non-profit: the Metropolitan United Church, St. Paul’s Basilica, St. Paul’s Catholic School, St. Mike’s Hospital, Fred Victor, Good Shepherd, the Moss Park Armoury, the adjacent public park, the large Moss Park Toronto Community Housing complex and the smaller social housing townhouses. All these establishments benefit the neighbourhood but stagger the commercial presence on Queen Street – and none would be paying the BIA levy. The onus would be on small shops already struggling to survive in the post-Covid world.

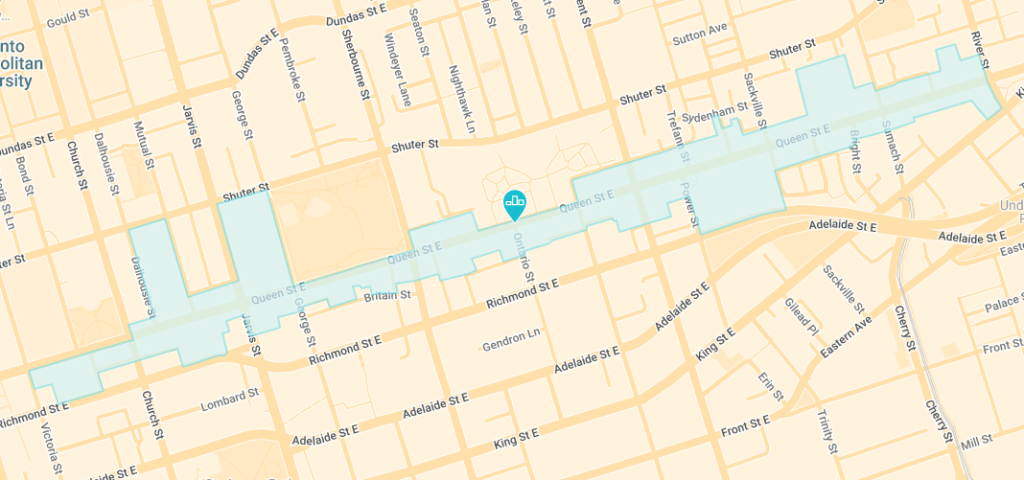

The current Queen East BIA boundaries stretch from Victoria to River Street. Photo courtesy of TABIA

Foot traffic along the Queen East strip varies wildly. The closer to Yonge Street, the better the chances of seeing life on the streets. But east of Parliament is a veritable ghost town. Businesses must bring in their own clientele or cater to a specific market (like dog owners) to survive. A BIA might improve this with clever street animation strategies, but without businesses to draw crowds, such as the Dominion bar, which closed a year ago, this part of Queen East will continue to struggle.

What about Queen East’s identity that screams historic? Yes, there are lovely examples of late 19th-century commercial buildings, often willfully neglected. In fact, Queen and Sherbourne has some of the most extraordinary testaments to Toronto’s Victorian past precisely because the city wrote off the area many decades ago.

The cumulative heritage value of the Queen East BIA strip would not warrant a historical district designation. No cohesive cultural thread unites the area, a problem when the title “historic” is plastered on the name of the organization being resurrected.

Granted, a lot has changed since the BIA’s founding in 2006. The amount of private and public investment coming to Queen East in the form of residential condominiums and a transit system, via Metrolinx, is definitely a game changer. But these aren’t recipes for success. The benefits of more people on the street are still many years out.

Could the BIA cough up the “modest” $300,000 the councillor’s office targets and survive long enough to reap the gains of gentrification?

If the city is interested in revitalizing the Queen East strip, why not invest $300,000 itself to save the backs of small businesses? With an annual budget of $17 billion, the city surely has enough money to host a small festival or pilot a street animation project. If successful, it would help convince members of the benefits of capital investment.

With all the private development in the area, Section 37 funds, extracted from developers, could be channeled to improve the business community. If Dixon Hall, a large non-profit organization, can receive $500,000 to subsidize renovation at its Sumach Street location, then businesses at Queen and Sherbourne, fending off drug dealers daily, are deserving of support.

There is no denying that Queen East is in dire need of a renaissance. How to bring about change needs to be well thought out, sincere and practical. If Councillor Moise thinks resuscitating a failed business organization will be the panacea for Queen East’s woes, he’s going to have to come up with a clear and detailed answer as to how it will help.

Andre Bermon is the publisher/editor of the bridge, and former president of the Corktown Residents and Business Association.

- Correction: The Historic Queen East BIA went into dormancy in 2008, not 2011 as was previously reported.