By Andre Bermon, Publisher

–

Here we go again. Another attempt to enact some direction in downtown planning and it gets charley-horsed right out of the gate.

The King-Parliament Secondary Plan, a set of guidelines approved by City Council in July, will be challenged by developers at the Ontario Land Tribunal on December 7. As did the St. Lawrence Historical Conservation District before it, the King-Parliament Secondary Plan has aroused developer ire because it attempts to direct growth in an era of unbridled development.

Among the 43 appellants listed, many are subsidiaries of major investment firms, developers or non-profit enterprises, such as the Kielburgers’ WE to ME foundation, which recently sold buildings near Queen East and Parliament streets. Notable developers on the list include First Gulf, Brad J. Lamb, Alterra, Lanterra, Dream, Tricon, One Properties, Markee and Allied Properties.

Each time the city approves a set of planning guidelines to manage developer expectations and protect heritage, it gets shot down by a litany of appeals. With every verdict, the provincial land tribunal waters down local planning tools, exempting developers from the will of the people. It’s a wonder that communities bother participating in city-led consultations when ultimately, a consortium of developers with a phalanx of lawyers has the final say.

The problem lies in the province’s controlling relationship with its municipalities. In adopting zoning bylaws governing land use, cities must take their cues from Queen’s Park. Layers of planning framework exist starting from the Provincial Policy Statement to the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe, and all the way down to minute Policy Areas, such as for a portion of Queen Street East, for example, compiled in district Secondary Plans.

Each plan must conform to the higher-level policies. This inevitably leads to conflict when provincial goals directly contradict local needs and wants. The Ford government is dead set on densifying our downtown, explicitly so in its Provincial Policy Statement. This gives developers the upper hand when appealing municipal bylaws at the Ontario Land Tribunal, formerly the Local Planning Appeal Tribunal.

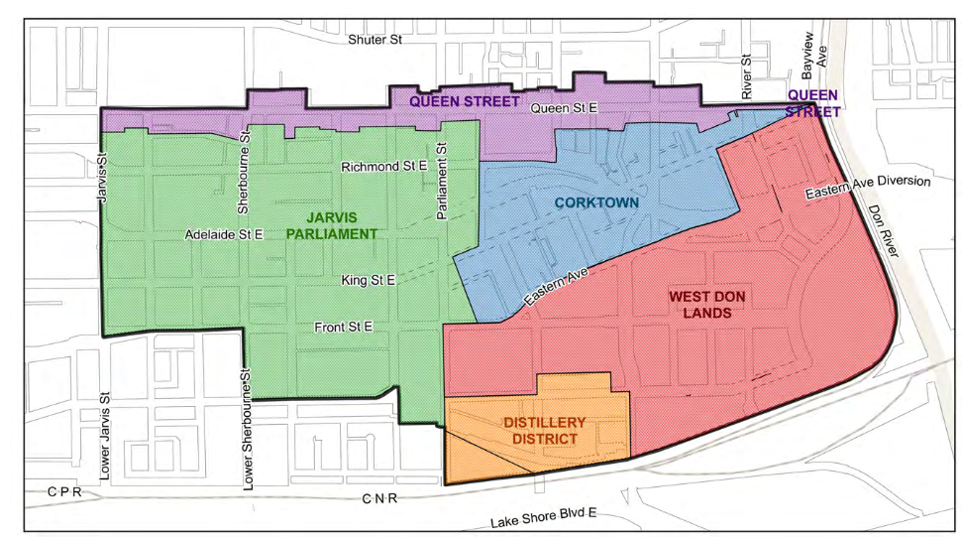

Toronto’s King-Parliament Secondary Plan was a mid-1990s response to former industrial zones of the downtown east emerging as potential investment opportunities. Historic neighbourhoods like Corktown and future communities such as the Distillery District were targeted for commercial and residential growth.

Since then, a lot has changed.

In 2018, City Planning undertook extensive consultation to update the plan and reflect the area’s new realities. Planners promoted key characteristics of the downtown east, such as heritage, parks and public realm, as well as an array of bylaw amendments dictating built form. Rules on building height and mass vary depending on the policy area. In Corktown, new structures are to be low- to mid-rise, whereas the Old Town area, encompassing streets such as Richmond, Adelaide and King East, have a wider range of allowable heights, up to 90 metres (27 storeys).

The city’s tools for shaping the King-Parliament planning area are far from novel, but its emphasis on preserving neighbourhood character while anticipating future density, makes the document all encompassing. When council approved the plan, residents and community groups that had participated in nearly four years of city-led consultations considered it a major victory.

Alas, the developers cried havoc, and let slip their dogs of appeal.

Each appellant will attempt to convince the tribunal adjudicator that their proposal should be exempt from the plan’s “overly proscriptive” policies. Many will argue that local bylaws don’t conform to the relevant planning framework. This is a process that may take a year to conclude.

The developers’ strategy has worked repeatedly in the past. In the meantime, the appeals are keeping the King-Parliament Secondary Plan in limbo, weakening its ability to protect unique neighbourhood assets from impending uniformity.